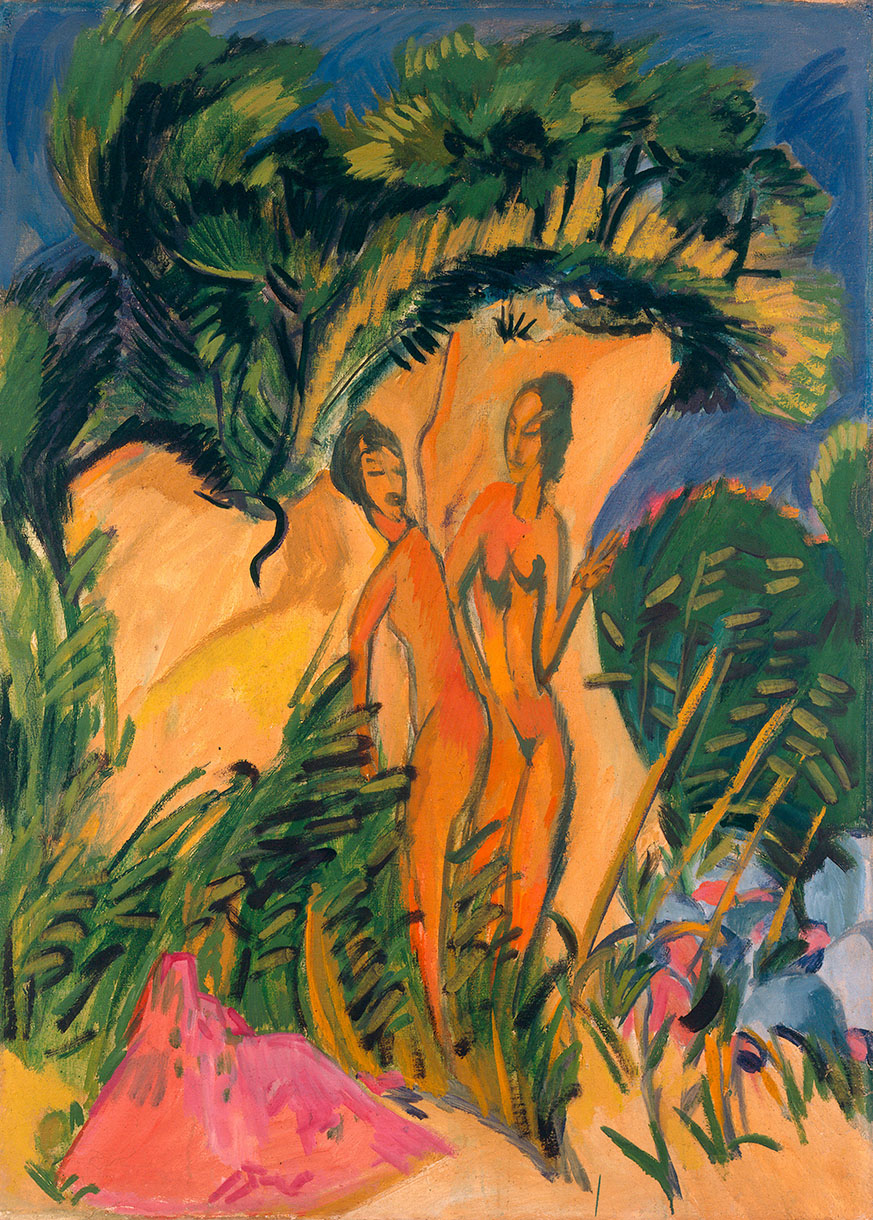

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Nude Girls at Fehmarn. Oil on canvas. Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg. Photo: Lehmbruck Museum

This is an excerpt from Meike Hoffmann’s catalogue essay “The Children Who Modelled for Brücke: Observations from the Perspective of AestheticTheory and Moral Ethics”.

Art in Conflict With the Law

Runtime: 03:42

Narrator: The Brücke artists soon clashed with the law. As Fritz Bleyl recounts in his memoirs, he designed a poster with a female nude for the group’s first exhibition in Dresden in 1906, only to have it banned from the streets by the police.

The poster fell prey to art censorship implemented a few years earlier at the behest of Kaiser Wilhelm II in the wake of judicial proceedings against a pimp named Hermann Heinze and his wife in Berlin’s red light district.

The case brought to light a “horrifying picture of moral conditions”, which the Kaiser seized upon to rein in the modern art he so detested. The Lex Heinze, an amendment to the Criminal Code enacted in February 1900, was designed to combat pornography, procuring, and pimping, but it also brought tougher surveillance of the art and theatre worlds.

The provision on “art and shop windows” made it an offence to exhibit, sell, broker, or announce “indecent writings, pictures, or depictions in places accessible to the public”. According to Bleyl, his poster met the criterion because its particular use of light and shade “created the impression of hairy genitals on the female figure”.

A few years later the painters were in trouble with the law again. After spending the summer of 1909 at the lakes in Moritzburg in the company of their models without arousing any suspicion, they received a visit from the local constable the following summer. This time the two daughters of a performing artist were present: “He asked us what we were up to. Well, we were dumbfounded. The two girls hastily donned their bathrobes and we stood before him, as he saw it, caught in the act of sinning indecently against morality,” Max Pechstein later recalled.

The policeman confiscated a painting by way of evidence and reported a criminal offence. This time the artists were severely rattled because the courts of the period had the power to hand down a “maximum custodial sentence of ten years” for “immoral acts” or “tolerating immoral acts” with “persons under the age of fourteen”. Even moving a group nude drawing session into the open air was enough to trigger criminal proceedings: “Causing a public nuisance in the form of an indecent act is subject to a prison sentence of up to two years.”

Max Pechstein, the only member of the group who had professional training as an artist, asked one of his former professors at the Dresden Art Academy to confirm his status, thereby averting a trial before the high court in the city. This indicates that there was some room for manoeuvre between the moral code negotiated by society and the practice of the courts.

According to Pechstein’s recollection of the matter, the artists had shown the constable all proper respect for his duties as an officer of the law: they made the children put clothes on and moved their base to an island that was shielded from the public gaze by vegetation. On the other hand, they sneered at the threat of sanctions as they were confident of their artistic freedoms.

After all, the Lex Heinze amendment with its extra restrictions on art and theatre life had provoked such a vehement wave of protest in recent years that Kaiser Wilhelm had been forced to backtrack on many points.