Hans Haacke, The Road to Profits is Paved with Culture, 1976. © Hans Haacke/Bildupphovsrätt 2025

The Road to Profits is Paved with Culture, 1976

Hans Haacke

The company Allied Chemicals used cultural sponsorship to polish its reputation, while environmental scandals painted a different picture. Curator Jo Widoff talks about Haacke’s classic work.

Runtime: 02:16

Jo Widoff: It’s rare that we acquire works to add to our historical collection. There are many reasons for this: the most significant works are already held in other museums; they’re already incredibly expensive; previous oversights aren’t easily corrected.

Art museums often speak about “gaps” in their collections—why don’t we have more works by Latin American modernists, or why have certain artists been overlooked? At the same time, a museum collection is a living organism, shaped over generations. Gaps appear, and strengths and idiosyncrasies emerge. Working with a collection is, therefore, a dynamic process—a task of relating to history and the future.

My name is Jo Widoff, and I am a curator responsible for international art up to 1989. Together with my colleagues, I seek out works that wedge themselves into the space between established art history and the present moment. Hans Haacke’s The Road to Profit is Paved With Culture (1976) is one such work.

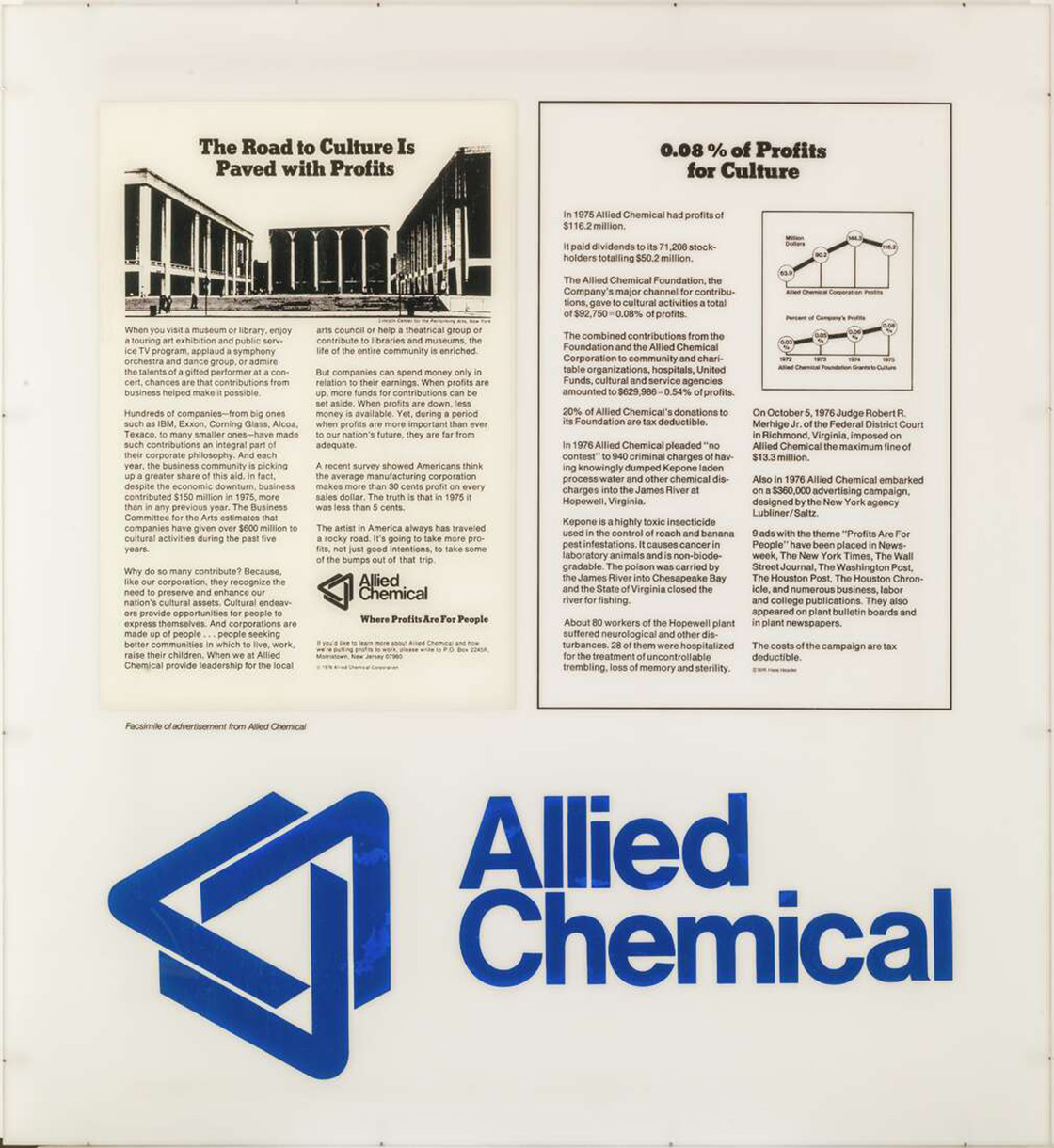

Hans Haacke is a German-US artist known for uncompromising work that scrutinizes the art world’s own power structures. The Road to Profits is Paved With Culture is part of a larger series in which the artist confronts the way big corporations flaunt their philanthropic ambitions, critiquing corporate sponsorship’s role in shaping culture. Haacke’s framing makes it clear that such sponsorship is not charity, but strategic investment in the brand, with the resulting cultural capital sometimes used to deflect criticism and create public goodwill.

Using Allied Chemical’s own materials, Haacke refrains from editorializing, letting the corporation’s rhetoric speak for itself. This strategy critiques both the companies and the cultural institutions that accept and normalize such funding. The work, which was made in the mid-1970s when ethical questions around the financing of culture were under intense debate, directly challenges the idea that the art world is neutral, asking if there really is such a thing as free art.

Haacke’s work is part of art history, but the questions he asks have never been more urgent for artists, audiences, and art institutions the world over.