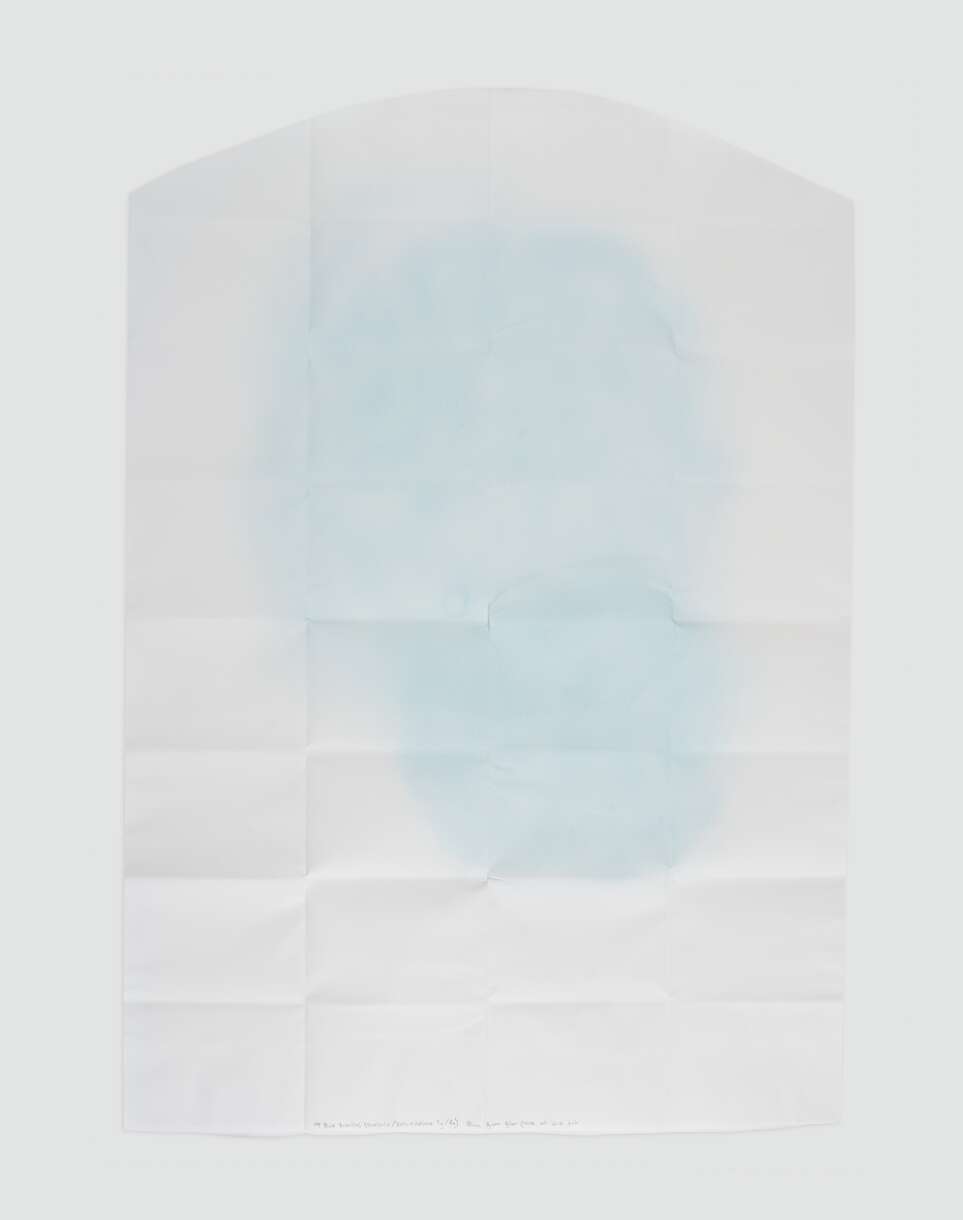

D Harding, 104 Blue Breaths (Tenofovir/Emtricitabine 9g/6g), 2022. © D Harding/Bildupphovsrätt 2025

104 Blue Breaths (Tenofovir/Emtricitabine 9g/6g), 2022

D Harding

Paper Conservator Alison Norton must balance the risk of damage with the artist’s wish to challenge the art world’s view of transport and climate.

Runtime: 03:32

Alison Norton: Hej, I am Alison Norton, the paper conservator at Moderna Museet, with responsiblity for the collection of over 60,000 works of art – prints, drawings, paintings, posters, artist and sketch books on all different kinds of paper and card.

When 104 Blue Breaths was acquired in late 2023, I was intrigued both practically and philosophically. I was asked for thoughts regarding the artists’ practice and wishes. One request is to minimize the use of resources, with art market and museum systems simplified and their hierarchies of economics and access reduced. This means no specialized art handling transport but sending the artwork via a registered postal service, such as DHL or Fedex. For a conservator, whose role is to minimize risk, this was more than thought-provoking – but supporting the artist’s intent and activism was essential. The work was sent from Australia and finally arrived safely in early 2025.

I was nervously expecting a damaged envelope, but the work came safely in a sturdy archival box. The next stage was unpacking. The work is folded multiple times in and onto itself. Unfolding required great care and caused a few. The heavy watercolour paper is strong and long-lasting, yet folds had caused small splits at the centre. These have been partly stabilized, but the folds and now tears are integral parts of the work’s meaning and history, echoing Aboriginal traditions of portability. Ideally, the piece is refolded for storage and transport.

The artwork is made on thick cotton paper with a slightly rough texture. Its media is unusual: a medication ground into pigment, normally used both in the treatment of HIV infection and as preventive therapy (PrEP) to reduce the risk of contracting HIV. After research, no extraordinary health and safety risks were identified, though it remains best not to touch the surface.

The work was created using an atomizer – transforming paint -pigment in a liquid adhesive – into fine droplets and applying them with breath. This technique connects to Indigenous traditions where pigments, such as ochre, were breathed onto stencils in rock art. Breath itself becomes both medium and meaning.

Harding’s blue surfaces have an ethereal, delicate quality, balanced by the strength of the large-format paper.

Handling the work is professionally challenging, ensuring the paper is not creased and the tears don’t get worse. Only five nails have been used before, and these holes are already slightly damaged. The weight of the paper gradually pulls down enlarging the holes. We have emulated Hardings use of horseshoe nails, rectangular not circular heads, for the presentation.

A first artist interview has occurred, a common practice in contemporary art conservation. These conversations ensure documentation of how works should be preserved, material and non-tangible, and presented as intended: whether the sheet must remain folded, how it should be exhibited, and how to balance risk in future loans or transport.

104 Blue Breaths is for me a personal favourite – fragile yet powerful, grounded in cultural tradition while provoking new ways of thinking about art and conservation practice.