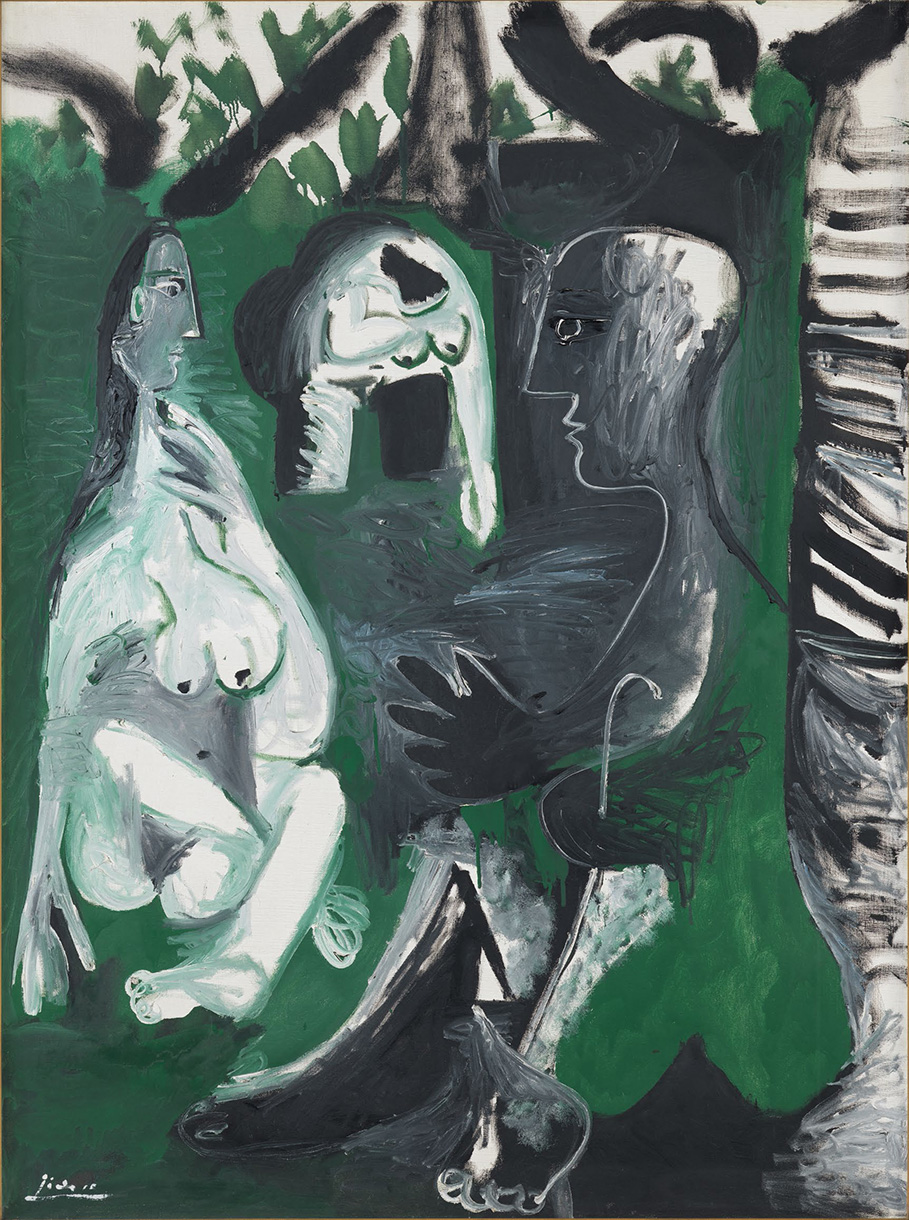

Pablo Picasso, Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), 30 July 1961. Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark. Donation from The Louisiana Foundation. © Succession Picasso/Bildupphovsrätt 2025. Photo: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Danmark

Luncheon on the Grass, 1961

Pablo Picasso

Runtime: 01:54

Narrator: When Picasso first saw Édouard Manet’s monumental Luncheon on the Grass, he wrote on the back of an envelope: “When I see Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, I tell myself there is pain ahead.” The remark would prove prescient. More than twenty-five years later, between 1954 and 1962, Picasso returned repeatedly to Manet’s canvas, dismantling it piece by piece.

In its own time, Manet’s painting caused a scandal: a naked woman among fully dressed men, set in an everyday landscape. For Picasso, it offered a way to confront painting’s fundamental questions – how to depict the body, how to see and be seen, and where the border lies between reality and fiction.

In his studio, Picasso produced more than 150 variations on Luncheon on the Grass. He painted, drew, etched and even built the figures in cardboard, moving them around and photographing them in the garden. Each version became an experiment – at times ironic, at times direct, at times playful. The woman who meets the viewer’s gaze in Manet’s painting here turns toward the man opposite her. Her features can suggest those of Jacqueline Roque, Picasso’s wife, and the male figure has often been interpreted as recalling the artist.

In 1962, Picasso collaborated with the Norwegian artist Carl Nesjar to translate his cardboard models into monumental concrete. The sculpture group Luncheon on the Grass, installed in the garden outside Moderna Museet, brought the figures fully into daylight – into the nature Manet had only suggested on canvas.

For Picasso, working with Luncheon on the Grass became a dialogue with the history of painting, but also a test of his own powers. It is not a tribute to Manet but a sustained encounter across a century – over the gaze, the body and the freedoms of painting.