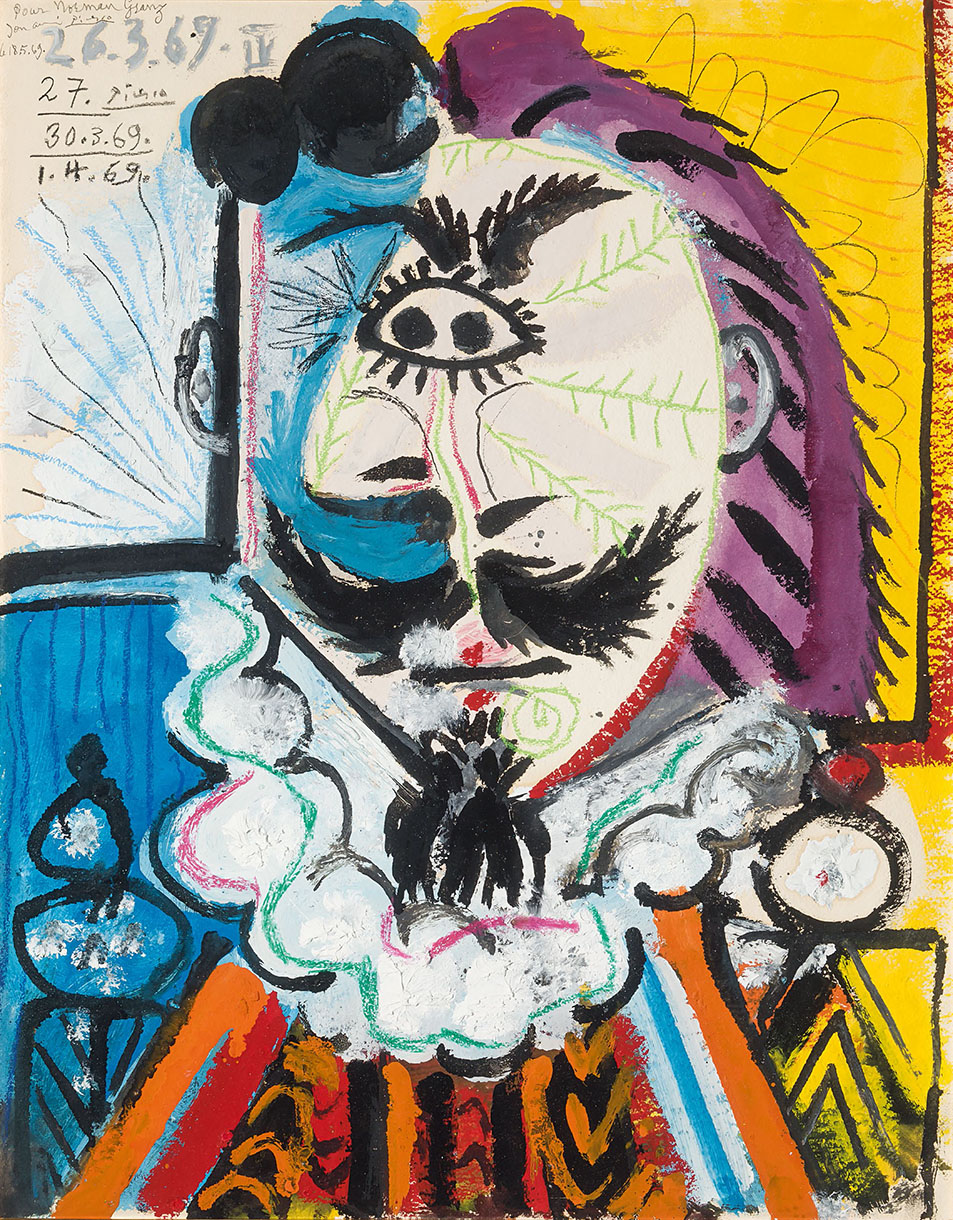

Pablo Picasso, Tête d'Homme (Head of a Man), 1969. © Succession Picasso/Bildupphovsrätt 2025. Photo: Rauno Träskelin. Private Collection.

Head of a Man, 1969

Pablo Picasso

Runtime: 01:49

Narrator: When Picasso painted his musketeers in the late 1960s, he drew on a world he had carried within him for decades. After a stomach operation in late 1965, he spent several months focusing on drawing, printmaking, reading and watching television. He reread Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers and saw similar tales of sword-wielding heroes and court intrigues on French television. From this blend of adventure and popular culture emerged a new figure – the ageing artist’s alter ego, armed with a brush rather than a rapier.

The musketeers provided a motif through which Picasso could play with historical types of masculinity. This Head of a Man recalls the Spanish courtiers painted three centuries earlier by Diego Velázquez – men with deep-set gazes and aristocratic bearings. But while Velázquez portrayed men of power, Picasso reimagines them as vivid, stylised characters with bold colour and line.

Velázquez had accompanied Picasso throughout his life. As a teenager, on his first visit to the Prado Museum in 1895, his father urged him to study the artist closely. There, before Velázquez’s court jesters, ladies-in-waiting and nobles, a lifelong conversation began. Over the decades, Picasso returned to these figures – not to imitate them but to explore what it meant to be a painter in their wake. When he later created his musketeers, they became a continuation of the Spanish tradition he had encountered in Madrid.

When Picasso showed his musketeers to friends, he would remark: “With this one you’d better watch out. That one makes fun of us. That one is enormously satisfied. This one is a grave intellectual. And that one, look how sad he is, the poor guy. He must be a painter.”